Mount Vernon in the Revolutionary War Era

[The following excerpts are taken from The Home of Washington; or Mount Vernon and Its Associations, Historical, Biographical, and Pictorial by Benson J. Lossing. Detailed in the excerpts is the life at Mount Vernon before, during, and after the Revolutionary War. For the full account of Mount Vernon, click HERE.]

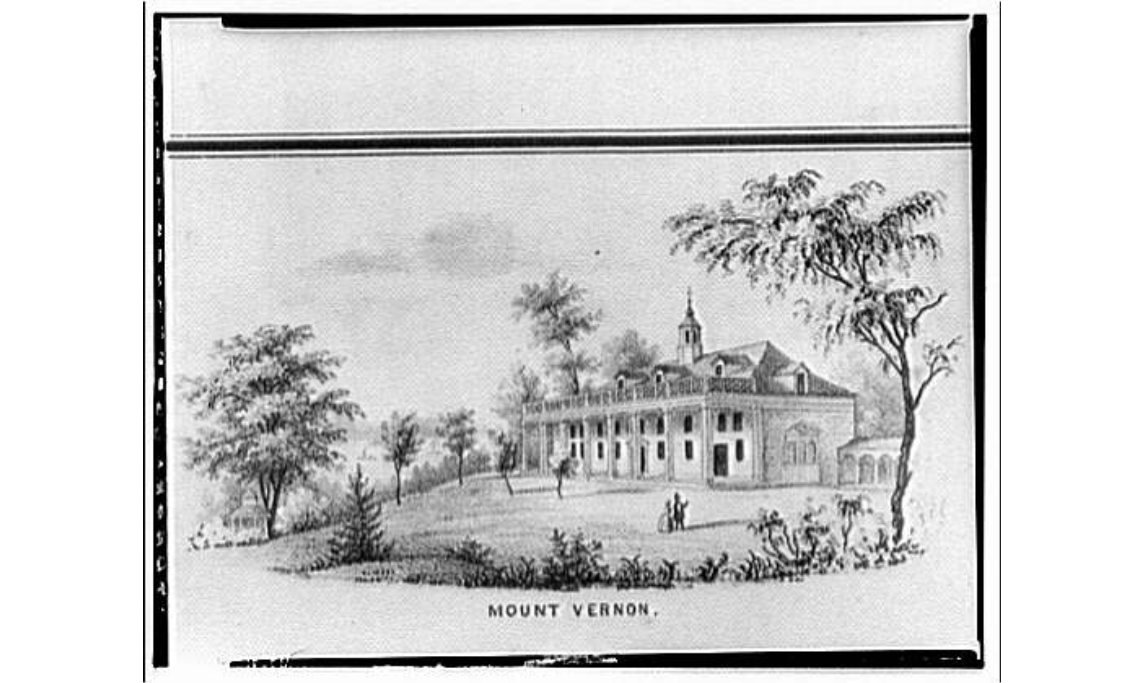

(Drawing of Mount Vernon | Source: Library of Congress)

So carefully did Washington manage his farms, that they became very productive. His chief crops were wheat and tobacco, and these were very large—so large that vessels that came up the Potomac, took the tobacco and flour directly from his own wharf, a little below his deer-park in front of his mansion, and carried them to England or the West Indies. So noted were these products for their quality, and so faithfully were they put up, that any barrel of flour bearing the brand of “George Washington, Mount Vernon,” was exempted from the customary inspection in the British West India ports…

And now the dawn of great events, in which Washington was to be a conspicuous actor, glowed in the eastern sky. From the Atlantic seaboard, where marts of commerce had begun to spread their meshes (then small and feeble) for the world’s traffic, came a sound of tumult; and the red presages of a tempest appeared in that glowing orient. At first, that sound was like a low whisper upon the morning air, and, finally, it boomed like a thunder-peal over the hills and valleys of the interior, arousing the inhabitants to the defence of the immunities of freemen and the inalienable rights of man…

An extravagant administration had exhausted the national exchequer, and the desperate spendthrift, too proud to borrow of itself by curtailing its expenditures, seemed to think nothing more honorable than a plea of bankruptcy, and sought to replenish its coffers by taking the money of the Americans without their consent, in the form of indirect taxation. This was in violation of the great republican postulate, that

TAXATION AND REPRESENTATION ARE INSEPARABLE…

At Mount Vernon there was a spirit that looked calmly, but not unconcernedly, upon the storm, and, with prophetic vision, seemed to perceive upon the shadowy political sky the horoscope of his own destiny. Washington was a member of the Virginia House of Burgesses, and had listened from his seat to the burning words of Patrick Henry, when he enunciated those living truths, for the maintenance of which the husbandman of Mount Vernon drew his sword a few years later. His soul was fired with the sense of oppression and the thoughts of freedom, yet his sober judgement and calculating prudence repressed demonstrative enthusiasm, and made him a firm, yet conservative patriot…

The sports of the chase, social visiting, and almost every amusement of life now ceased at Mount Vernon. Grave men assembled there, and questions of mighty import were considered thoughtfully and prayerfully, for Washington was a man of prayer from earliest manhood…

Lonely was the mansion at Mount Vernon without the master during the seven years and more that the war lasted… Lund Washington, the master’s relative and friend, was the faithful manager of the estate, and he scrupulously obeyed the injunction of the owner, who said: “Let the hospitality of the house, with respect to the poor, be kept up. Let no one go away hungry. If any of this kind of people should be in want of corn, supply their necessities, provided it does not encourage them in idleness…”

It was on Christmas eve, 1783, that Washington, a private citizen arrived at Mount Vernon, and laid aside forever the military clothes which he had worn perhaps through more than half the campaigns of the war just ended. Around them clustered many interesting associations, and they were preserved with care during the remaining sixteen years of his life…

”Freed from the clangor of arms and the bustle of a camp,” he wrote to the wife of Lafayette, in April, after receiving information that the marquis intended to visit America soon—”Freed from the cares of public employment and the responsibility of office, I am now enjoying domestic ease under the shadow of my own vine and my own fig-tree; and in a small villa, with the implements of husbandry and lambkins around me, I expect to glide gently down the stream of life, till I am entombed in the mansion of my fathers…

Come, then let me entreat you, and call my cottage your home; for your own doors do not open to you with more readiness than mine would. You will see the plain manner in which we live, and meet with rustic civility; and you shall taste the simplicity of rural life…”

”A glass of wine and a bit of mutton are always ready, and such as will be content to partake of them are always welcome. Those who expect more will be disappointed.”