The Forgotten History of Traveller’s Bones

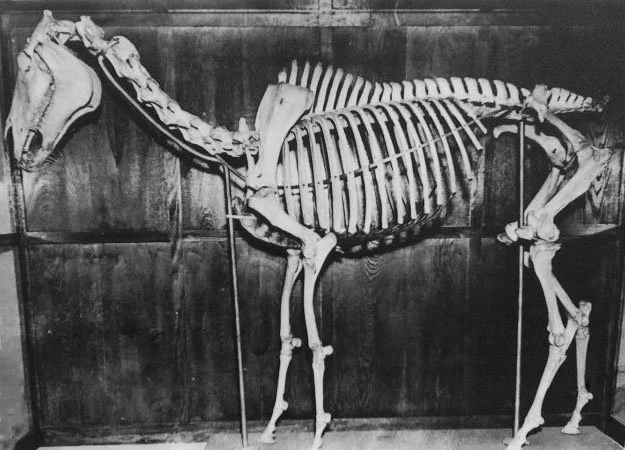

(Travellers bones on display in Lee Chapel museum, prior to 1961 renovations. | Washington and Lee University)

Happy Halloween! Keeping the season’s spirit in mind, we encourage our Lexington friends to stop by the grave of Traveller, Robert E. Lee’s beloved horse. Few students today know of Traveller’s life — and fewer still of his strange adventures after death. Indeed, that old horse has never quite rested easily.

We’ll spare the full tale of how Traveller’s remains were once — rather unceremoniously — tossed into a ravine in 1871. The real intrigue begins in 1907, when university officials resolved that, for the centennial of General Lee’s birth, his faithful horse should ride again, this time in skeletal form.

Traveller’s supposed remains were first put on display that year in what was then the Brooks Museum of Natural History, nestled in the historic Colonnade. In the 1920s, his bones were relocated to the newly opened (and now closed) museum beneath Lee Chapel.

Over time, a curious custom emerged: students whispered of the “Hoodoo” tradition, a desperate rite for good luck before exams. For fortune’s favor, they carved their initials into Traveller’s decaying bones. The ritual was publicly frowned upon, yet its grim allure spread quickly through the student body.

Decades of neglect — and the poor treatment of the remains by an earlier taxidermist — took their toll. By the early 1960s, Traveller’s skeleton had deteriorated into ghastly condition. When Lee Chapel underwent renovation, university officials quietly removed the remains from display, placing them in the basement of Baker Dormitory (since demolished, along with Davis Hall, to make way for the new Commerce School).

In July 2023, as editor of The W&L Spectator and an intern for The Generals Redoubt, I spent many hours researching the history of Front Campus monuments — including the 1971 gravesite of Traveller. As many readers will recall, university officials controversially removed and later replaced Traveller’s headstone that summer, sparking national and even international attention.

During that storm of discussion, an alumnus from the Class of 1967 wrote me an email titled “The Forgotten History of Traveller’s Bones.” His message revealed a chilling memory — a firsthand account that may be the spookiest chapter of all:

The recent mysterious removal of a plaque involving Traveller seems symptomatic of the current administration's muted embarrassment about the history of W&L. But some of that same attitude (quiet suppression of details about the college's original identity) has been floating around Lexington for a long time:

I lived for two years (1964-66) in the Baker dorm before moving over to Davis for my last year (1966-67). Have they changed the names of those two dorms yet, or are Baker and Davis now so forgotten that there is no longer any reason to bother deleting their names from the buildings? At the end of the 1964-65 school year, I decided to move some of my stuff -- for temporary storage -- to the basement of Baker (we were allowed to do that then).

While I was moving my things, I was horrified to encounter, in the basement, a large glass case (randomly stored) containing the mounted skeleton of Traveller; his head had somehow become detached and had been placed on the bottom of the case, between his front feet. It looked to me like a long-neglected result of tasteless, antiquated taxidermy, where the skin had, at some earlier time, been removed because it was deteriorating, leaving only the poor horse's skeleton.

I told two or three of my friends about what I had seen, but I never said anything about it in public. I was ashamed for the university. A few years later, when I heard that they had finally buried Traveller's bones, I was relieved, but I still didn't say anything about how his remains had been treated before.

Good luck with monitoring all the stealthy efforts at erasing the past.

By 1971, complaints from alumni had grown too loud to ignore. President Huntley authorized the United Daughters of the Confederacy to give Lee’s favorite horse a proper burial beside the Lee Family Crypt.

And so, the matter was laid to rest — at least for the next five decades.

Yet each Halloween, as the autumn wind sweeps through the Colonnade, one can’t help but wonder: does Traveller’s spirit still stir beneath the old stones of Lexington?

Historically,

Kamron M. Spivey, ’24

Executive Director

The Generals Redoubt