John W. Davis and the Steel Seizure Case

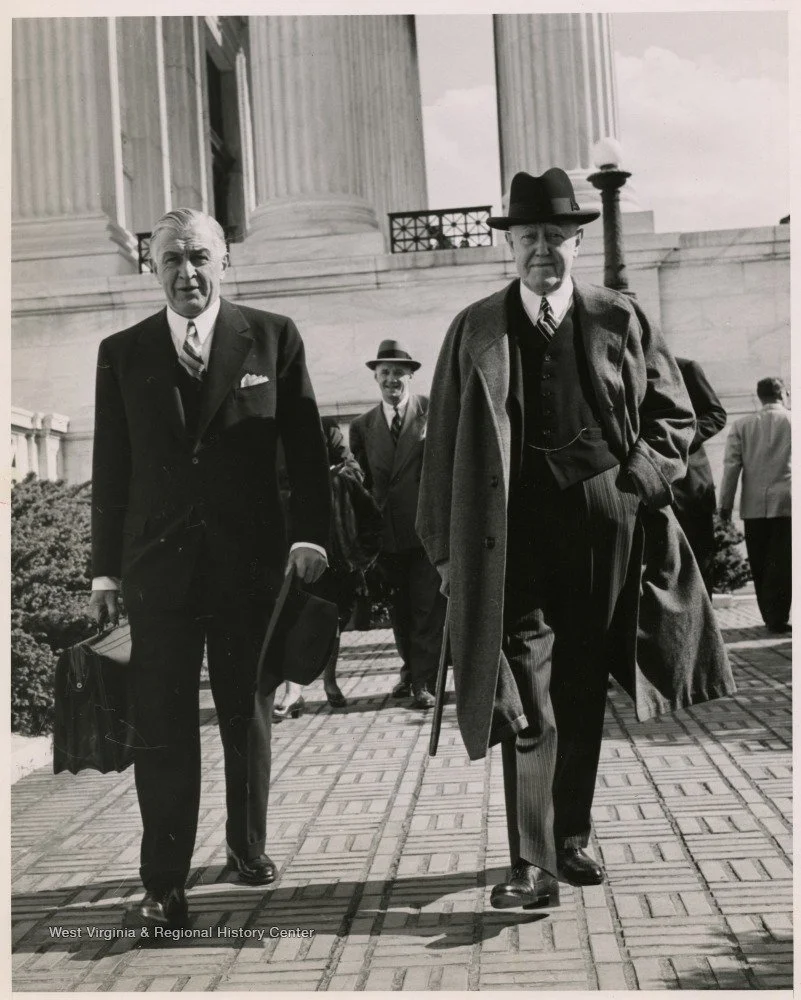

(John W. Davis and likely Theodore Kiendl at the Supreme Court after the Youngstown Steel Case, 1952. | West Virginia University)

With President Franklin Roosevelt’s landslide electoral victories in 1932 and 1936, the way was cleared for sweeping legislation that would forever change the American economic system. Conservatives, who rose in opposition to the New Deal, were forced to mount their battles in the courts. The most prominent leader of this conservative opposition was John W. Davis, the legendary Wall Street lawyer and former Democratic presidential nominee.

(President Calvin Coolidge had decisively defeated Davis in 1924).

Before FDR’s election, Davis had warned against President’s Hoover’s moves toward government management of the economy. In a letter to Walter Lippmann, Davis wrote, “Nothing but mischief can come from any government attempting tasks which lie beyond its power to accomplish.”

In the 1932 presidential campaign, Davis charged Hoover with “interfering with the inexorable laws of supply and demand. The error of the Republicans was their apparent determination to spend all we had and as much as we could borrow.”

In 1932, Davis urged the Democratic party “to eschew taxing the few for the benefit of the many and resume its rightful place as the militant champion of local self-government.” Having been the primary author of the conservative 1932 Democratic Party platform, Davis was shocked by FDR’s quick abandonment of the platform.

It was soon clear that FDR was to reach far beyond anything Hoover had imagined.

By late 1933, Davis had become convinced that the New Deal was fast becoming a “wild reach for governmental power and a dream of a regimented economy under the control of a super state.” Davis took the lead in opposing FDR in public speeches, in forming The Liberty League, and, most importantly, in challenging New Deal legislation in the courts.

On several occasions, Davis defined his personal credo as follows: “I believe in the Constitution of the United States; I believe in the division of powers that it makes … I believe in the right of private property, the sanctity and binding power of contracts; the duty of self-help. I am opposed to confiscatory taxation, wasteful expenditure, socialized industry and a planned economy controlled and directed by government functionaries. I believe these things to be inimical to human liberty and destructive of American ideals.”

Predictably, it was not long before FDR had branded Davis “public enemy Number One,” a sobriquet Davis wore with some pride.

While the New Deal ended with WW II and the death of FDR, the battle against the expansion of government continued under President Harry Truman. One of the greatest chapters in American constitutional history is the 1952 Supreme Court case Youngstown Sheet and Tube Co. v. Sawyer. This case is frequently taught in US law schools and often cited in modern court cases.

Today, the most urgent question before the Court is the challenge to President Trump’s tariff policies, and the overarching constitutional issue is the limits on executive power.

While it is always difficult to predict how the Court will decide, one can look back for precedents. Challenges to executive authority are not new. Presidents have often sought to implement their policies by pushing the conventional limits of authority — sometimes successfully, sometimes not. Perhaps the most famous of such cases, Youngstown Steel, seems to offer many parallels to today’s tariff case.

Here is the story of Youngstown Steel

In late 1951, in the midst of the Korean War, President Truman faced an urgent dilemma. Collective bargaining between the nation’s steel companies and their unions had reached a stalemate. Management was unwilling to meet what they considered unreasonable wage demands, and workers were equally adamant that their demands were warranted. The President was committed to insuring the war effort had the necessary steel and equally committed to maintaining stable prices.

The most available potential remedy was for Truman to invoke the Taft-Hartley Act, which would Impose a mandatory cooling off period. However, Truman detested the Republican-sponsored Taft-Hartley Act and elected not to invoke it. After much public posturing on both sides, Truman announced that he was directing Commerce Secretary Sawyer to seize control of the steel mills.

As he pondered this unprecedented action, Truman received unofficial (and inappropriate) assurance from his old friend Supreme Court Chief Justice Fred Vinson. Vinson believed such a move would be upheld by the Court. In fact, the clear majority of the Court was now filled with liberal-leaning justices, who were generally sympathetic to Truman

The reaction in Congress was immediate. Within days, fourteen separate resolutions to impeach Truman were introduced. Lawmakers warned against “a trend toward dictatorship,” and Senator Pat McCarran warned, “We have lost the democracy that we have long loved.”

Sound familiar?

Meanwhile, the steel industry executives were astounded at the President’s action. Industry spokesman, Clarence Randall, responded, “I felt physically ill. It seemed to me that all I had learned of government from school days on, all that I had believed in with respect to the balance of powers … had suddenly been swept away.”

Up to this point, the steel companies had sought separate legal counsel from various sources, but they now consolidated their case and wisely asked John W. Davis, senior partner of Davis, Polk & Wardwell, to make the sole oral argument.

If ever there were the perfect confluence of events and the man, it was this case and John W. Davis. Now in his seventy-ninth year, Davis stood at the apex of the legal profession. A former Congressman, US Solicitor General, US Ambassador to the Court of St. James’, Democratic nominee for President in 1924, and senior partner of a major Wall Street law firm, he had argued 138 cases before the Supreme Court – more than anyone in modern American history.

In addition to being recognized as “the lawyers’ lawyer,” Davis was ideologically a Jeffersonian Democrat, who fervently believed in limited government and strict constitutionalism. As counsel to U S Steel and special counsel to Republic Steel, Davis had already submitted his private opinion written in the strongest possible terms, “There is not the slightest doubt that the President’s action is without legal warrant – constitutional or statutory. It is an act of pure usurpation.”

On May 12, 1952, Davis delivered an eighty-seven-minute argument before a packed court chamber. Speaking with heartfelt conviction, he declared Truman’s action not only “a usurpation of power without parallel in American history, but a reassertion of the kingly prerogative, the struggle which illumines all the pages of Anglo-Saxon history.”

As one news reporter wrote, Davis “seemed to personify the spirit of constitutionalism, his voice that of history itself.”

Davis proceeded to argue, “is it not an immutable principle that our Government is one of limited powers? Is it or is it not an immutable principle that we have a tripartite system of legislation, execution, and judgment? Is it not an immutable principle that the powers of a government are based on a government of laws – not of men?

In somber conclusion, Davis paused for effect and quietly quoted Jefferson, “In questions of power then let no more be heard of confidence in man, but bind him down from mischief by the chains of the Constitution.”

The Washington Post reported at the conclusion of Davis’s argument, “seldom has a courtroom sat in such silent admiration.”

Because of the urgency of the case, the Court rendered its ruling in less than thirty days. Chief Justice Vinson’s advice to President Truman proved to have been ill founded. The Court ruled 6 to 3 against Truman and his unprecedented seizure of private property.

This landmark ruling supported two key pillars of American conservatism – the sanctity of private property and constitutional restraint.

For many years Davis had defended them both:

In 1934 Davis wrote, “Property rights and human rights are not antagonistic, but parts of one and the same thing going to make up the bundle of rights which constitute American liberty. History furnishes no instance where the right of man to acquire and hold property has been taken away without the complete destruction of liberty in all its form.”

Throughout the Great Depression years, Davis warned that governmental powers were granted only by the Constitution and could not be justified by declaration of emergency.

This case enforced the bedrock principle that all Americans — and especially Presidents — must abide by the Constitution.

For American conservatives, John W. Davis stands tall in our panoply of heroes, and the Youngstown case was his finest hour.

Garland S. Tucker III graduated B.S., magna cum laude, Phi Beta Kappa, Washington & Lee University (1969) and M.B.A. Harvard Business School (1972). He is retired Chairman/CEO Triangle Capital Corporation, author of Conservative Heroes: Fourteen Leaders Who Shaped America- Jefferson to Reagan (ISI Books) and The High Tide of American Conservatism: Davis, Coolidge and the 1924 Election (Emerald Books).